Outcome-driven microscopy to guide cell biology#

Alfredo Rates, Josiah B Passmore, Lukas C Kapiten, Utrecht University

Outcome-driven microscopy#

Smart microscopes take microscopy automation to the next level by adapting and optimizing the acquisition based on the experiment in progress. Thanks to information about the sample, either by user input, previous experiments, or defined strategies, with smart microscopy it is possible to get as much information as possible, while reducing sample damage. But smart microscopy is not limited to observation, it can also be expanded to have control over the biology thanks to outcome-driven microscopy. Outcome-driven microscopy is a smart microscopy strategy where the automation of the microscope is not only to change the acquisition parameters, but also to interact with the sample using the microscope hardware. As it is known, parameters such as temperature, flow, illumination power or color are inputs that affect biological samples. If this effect is controlled and known, it can be used to drive the biological processes to desired states. Indeed, this is possible with optogenetics. In optogenetics, photo-controllable proteins are used to activate processes at the subcellular level when illuminated with particular wavelengths. These proteins are not only sensitive to wavelength but also to light intensity and spatial patterning. Thus, by controlling these parameters, optogenetics has the power to precisely control the biology of cells.

Modular Python platform for smart microscopy#

To achieve outcome-driven microscopy, we combine smart microscopy with optogenetics, changing the optogenetic signal on the fly, and having a feedback loop between the (cell) biology and the (microscope) hardware. For this, we developed a modular software architecture in Python.

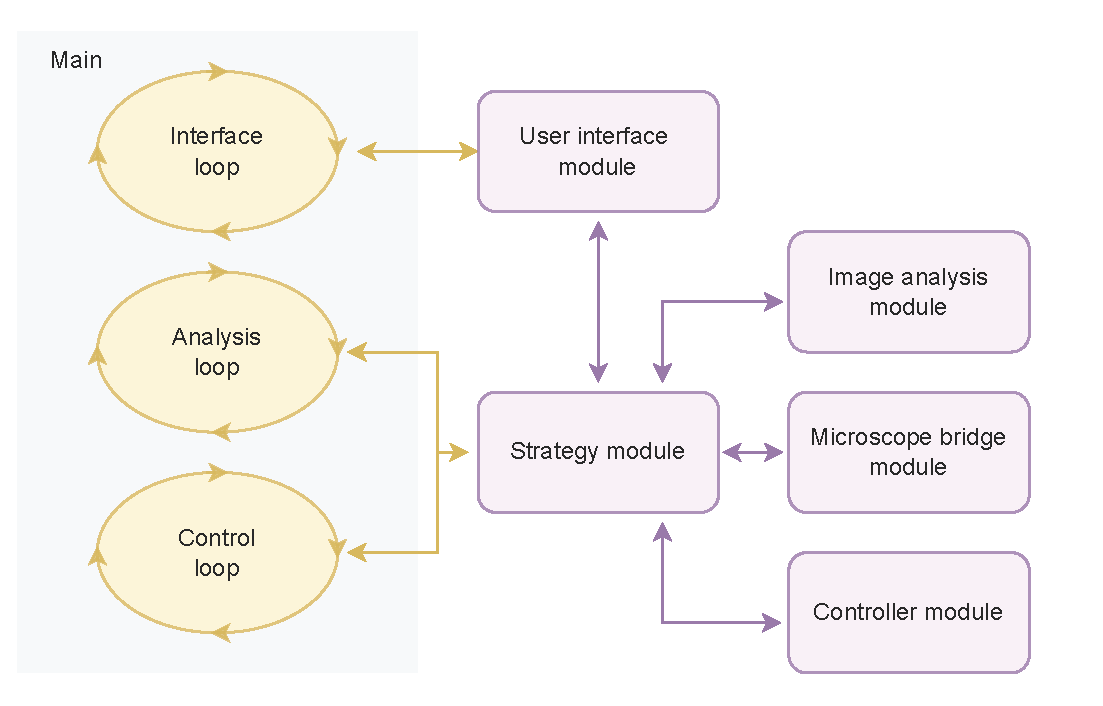

Fig. 1. Modules workflow, including the main.py script and its three internal parallel loops. The external modules in purple are imported as external libraries. Arrows represent communication lines between modules. Figure taken from [Passmore et al., 2024] with permission of the authors.

We developed a Python-based platform to perform automated, outcome-driven experiments. Our platform is organized into multiple modules, as described in Fig. 1. The platform has specific modules for user interface, image analysis (e.g., cell segmentation [Kirillov et al., 2023]), control strategy (e.g., PID controller [Ogata, 2001]), microscope communication (for specific hardware, e.g., Micromanager or Zen Blue Zen Blue), and outcome-driven strategy, where the algorithm for the specific experiment is defined (e.g., control cell expression to certain levels [Niopek et al., 2016]).

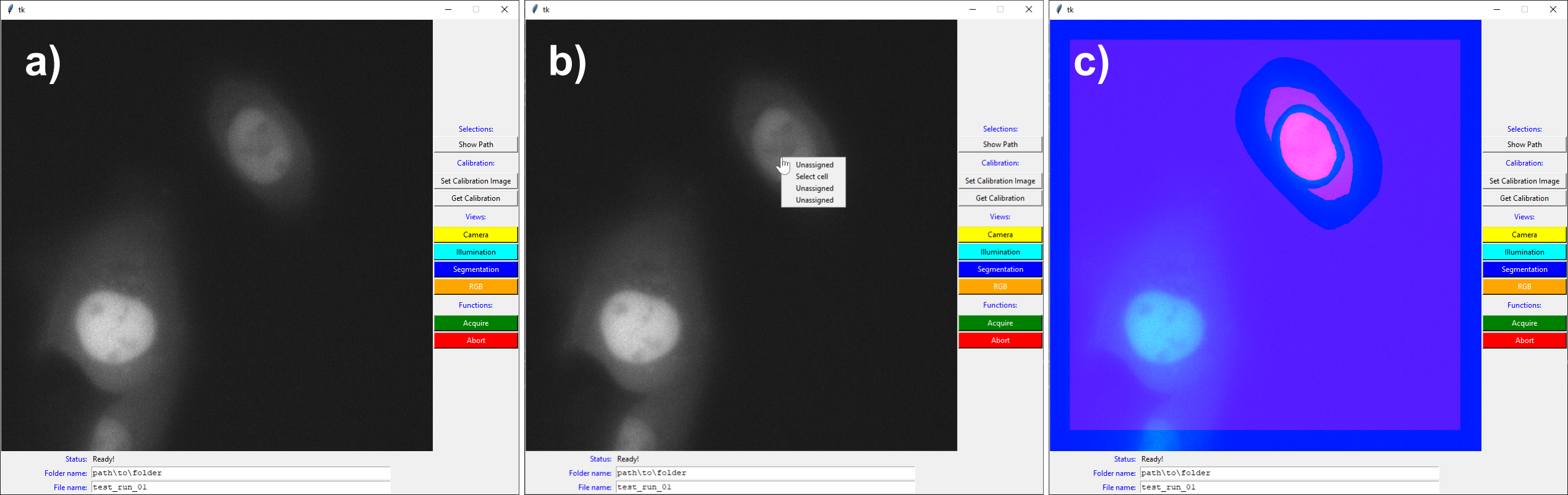

The user interacts with the platform through a main.py script and a graphical user interface (GUI). The main connects to the rest of the modules, including the GUI (see Fig. 2), and runs three parallel, asynchronous loops. The three loops consist of the interface loop, the analysis loop, and the control loop.

Fig. 2. Graphical user interface in three different states. A) when the software is just initialized, B) when right-clicking the cell to segment, including the drop menu, and C) the RGB visualization showing camera image, cell segmentation, and illumination pattern. In this case, the segmentation separated the cytosol from the nucleus, adding a margin in between. Figure taken from [Passmore et al., 2024] with permission of the authors.

The modules are imported to the main as external libraries based on the user input. Each module is structured as a class with an abstract class as a parent, meaning that they must have a list of functions and variables in order to communicate correctly with the rest of the platform. In case the user needs to develop a custom module, they can easily do it as long as the custom module includes these functions and variables. When running an experiment, the platform exports 4 main results. The first result is the time series acquisition, including channels and z-stacks, if previously defined. In addition, the platform exports the cell segmentation for each time step, the controller data (e.g., error, setpoint, laser power) as a .csv file, and the metadata of the experiment as a .json file.

Demonstration of outcome-driven microscopy using optogenetics#

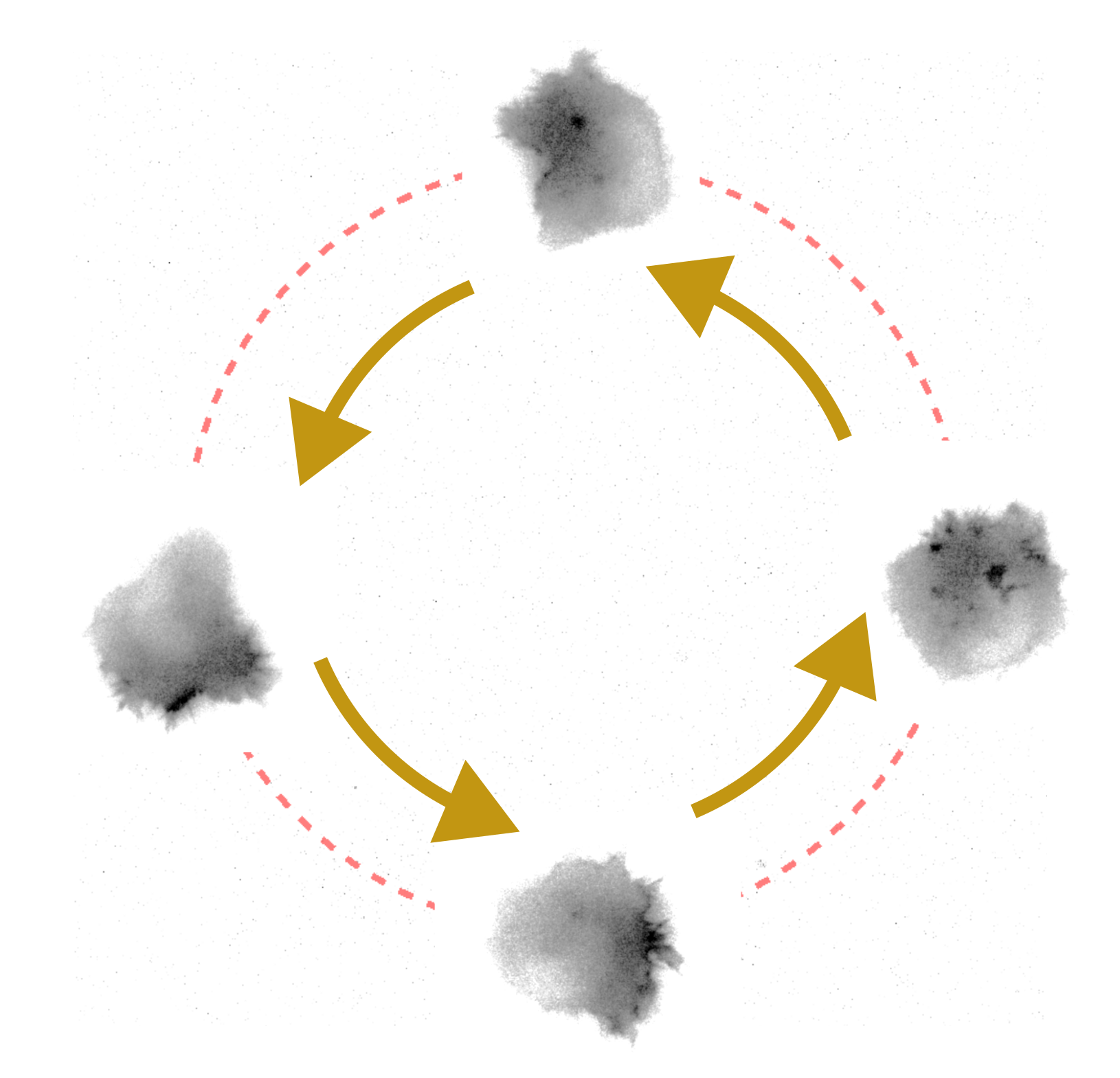

To demonstrate the power of outcome-driven microscopy, we applied our platform to directed single-cell migration, using an optogenetic construct to recruit the RAC1 effector TIAM1 to the plasma membrane. With outcome-driven microscopy, we adapt on the fly the area of the illumination within the cell, changing where the TIAM1 is recruited and thus drive migration in a specific direction. We change the illumination area of the optogenetic light using a digital micromirror device (DMD). For this implementation, the control module is based on a trajectory tracking controller based on the cell centroid relative to a path made up of setpoints, and the image analysis module uses the pre-trained AI segmentation method Segment Anything Model (SAM) [Kirillov et al., 2023] with a custom extension of its interface to track the cell. Thanks to our stable cell line and the outcome-driven platform, we could reliably guide cells around a specific path for many hours, maintaining a relatively consistent speed. Fig. 3 shows the cell migration path over the defined circle. This experiment was carried out in a Nikon Ti dual-turret inverted microscope and a Mightex Polygon 400 DMD, all controlled via Micromanager.

Fig. 3. HT1080 cell migrating in a circular path due to blue light stimulus. The area of illumination was constantly adapted using our outcome-driven microscopy platform. This measurement was performed in a Nikon Ti using a Mightex Polygon 400 for activation.

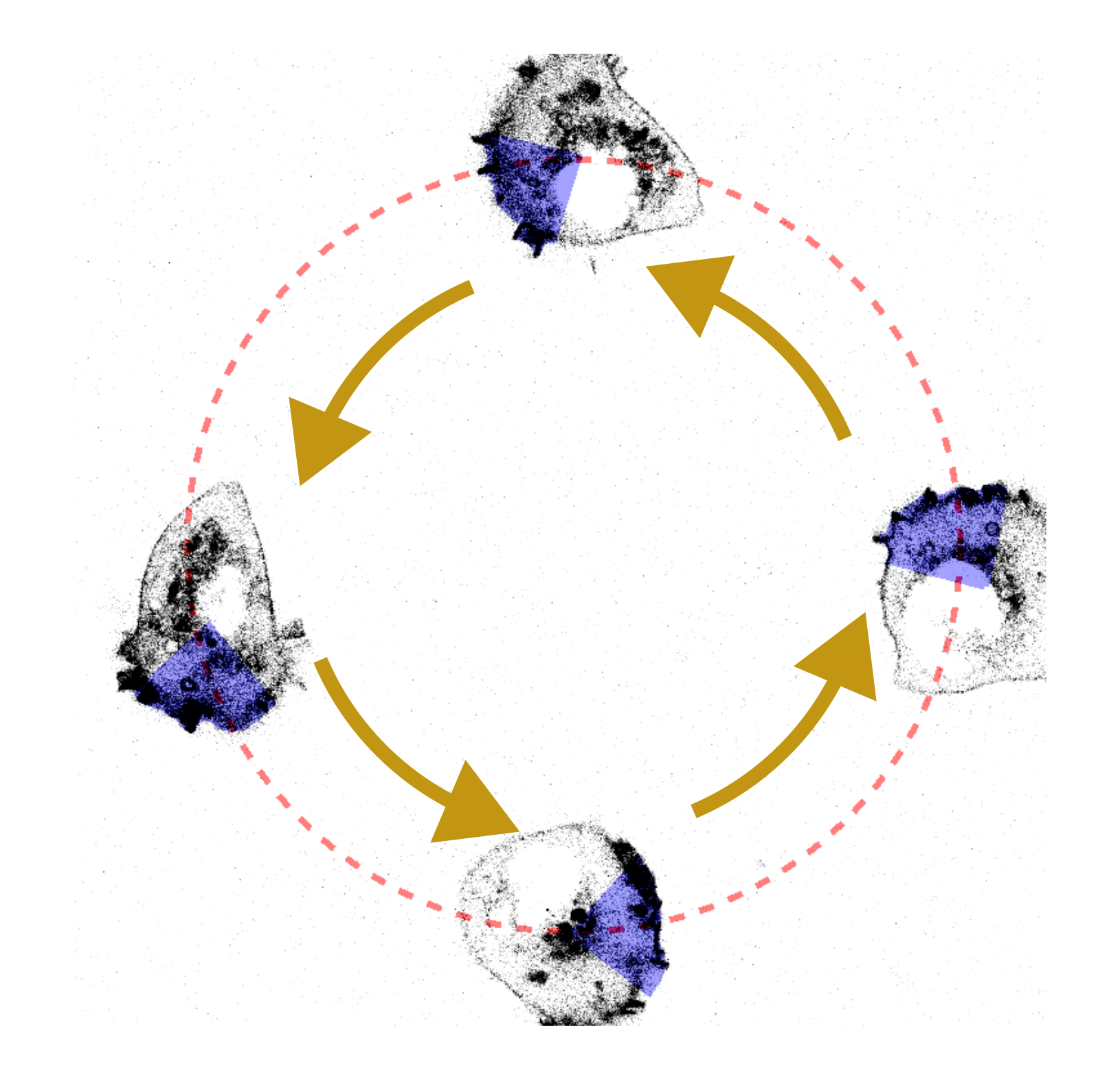

Thanks to our modular approach for the microscope bridge, we were able to adapt our communication scheme from a Micromanager-controlled microscope to a Zeiss microscope controlled by ZenBlue. We used an LSM-980 with AiryScan2 module, and instead of modulating the optogenetic light with a DMD, we adapted the region of interest (ROIs) of the confocal scanning. The results of the confocal-based cell migration is shown in

Fig. 4. HT1080 cell migrating in a circular path due to blue light stimulus, same as Fig. 3. This time, the measurement was performed in a Zeiss LSM980 and the activation was done scanning the area with the built-in blue light laser.

Limitations and outlook#

The advantage of modularity is not only that modules are exchangeable, but also that the platform is easily upgraded and improved. Among the improvements planned to the platform, we first intend to separate further the bridge module with the strategy module. In particular, the platform is structured around the multi-dimensional acquisition process of Micromanager. This structure is ideal for our outcome-driven experiments and can be translated to other microscopes easily, but it limits experiments to having a constant acquisition configuration, such as time step and number of Z-stack layers. To make our platform flexible, we plan to follow the structure offered by the pymmcore-plus library. pymmcore-plus is an alternative to Pycromanager to control Micromanager-compatible hardware, and is based around a queue of events instead of the multi-dimensional acquisition, i.e., a list of orders to give to the microscope. Furthermore, we plan to make a new interface based on the Napari [Sofroniew et al., 2025] library. Napari is an extensive visualization library, widely used for microscope data. This new interface offers more functionalities and interaction with the user, and it is also compatible with pymmcore-plus.

Alexander Kirillov, Eric Mintun, Nikhila Ravi, Hanzi Mao, Chloe Rolland, Laura Gustafson, Tete Xiao, Spencer Whitehead, Alexander C. Berg, Wan-Yen Lo, Piotr Dollár, and Ross Girshick. Segment anything. 2023. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.02643, doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2304.02643.

Dominik Niopek, Pierre Wehler, Julia Roensch, Roland Eils, and Barbara Di Ventura. Optogenetic control of nuclear protein export. Nature Communications, February 2016. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10624, doi:10.1038/ncomms10624.

Katsuhiko Ogata. Modern control engineering. Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 4 edition, November 2001.

Josiah B. Passmore, Alfredo Rates, Jakob Schröder, Menno T. P. van Laarhoven, Vincent J. W. Hellebrekers, Henrik G. van Hoef, Antonius J. M. Geurts, Wendy van Straaten, Wilco Nijenhuis, Florian Berger, Carlas S. Smith, Ihor Smal, and Lukas C. Kapitein. Outcome-driven microscopy: closed-loop optogenetic control of cell biology. bioRxiv, December 2024. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.12.628240, doi:10.1101/2024.12.12.628240.

Nicholas Sofroniew, Talley Lambert, Grzegorz Bokota, Juan Nunez-Iglesias, Peter Sobolewski, Andrew Sweet, Lorenzo Gaifas, Kira Evans, Alister Burt, Draga Doncila Pop, Kevin Yamauchi, Melissa Weber Mendonça, Genevieve Buckley, Wouter-Michiel Vierdag, Loic Royer, Ahmet Can Solak, Kyle I. S. Harrington, Jannis Ahlers, Daniel Althviz Moré, Oren Amsalem, Ashley Anderson, Andrew Annex, Peter Boone, Jordão Bragantini, Matthias Bussonnier, Clément Caporal, Jan Eglinger, Andreas Eisenbarth, Jeremy Freeman, Christoph Gohlke, Kabilar Gunalan, Hagai Har-Gil, Mark Harfouche, Volker Hilsenstein, Katherine Hutchings, Jessy Lauer, Gregor Lichtner, Ziyang Liu, Lucy Liu, Alan Lowe, Luca Marconato, Sean Martin, Abigail McGovern, Lukasz Migas, Nadalyn Miller, Hector Muñoz, Jan-Hendrik Müller, Christopher Nauroth-Kreß, David Palecek, Constantin Pape, Eric Perlman, Kim Pevey, Gonzalo Peña-Castellanos, Andrea Pierré, David Pinto, Jaime Rodríguez-Guerra, David Ross, Craig T. Russell, James Ryan, Gabriel Selzer, MB Smith, Paul Smith, Konstantin Sofiiuk, Johannes Soltwedel, David Stansby, Jules Vanaret, Pam Wadhwa, Martin Weigert, Jonas Windhager, Philip Winston, and Rubin Zhao. Napari: a multi-dimensional image viewer for python. 2025. URL: https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.3555620, doi:10.5281/ZENODO.3555620.